Understanding the consequences of enforcing the male gaze in photography.

This body of text focuses on the theory of “Male Gaze” from Laura Mulvey’s essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” [1] and how the understanding and realisation of this oppressive male gaze has transformed into the breaking down of heteronormative standards in photography, while ultimately creating a queer, female gaze. This chapter talks about the voyeurism of images, objectification and seeing the photograph within a narrative of the ruling ideology and habitus.

In the essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” Laura Mulvey describes how the male gaze creates a view of the female form as solely erotic for the male viewer in a voyeuristic manner. Whereas the female counterpart sees the photograph as observing themselves being viewed as a symbolic object either for the pleasure of the opposite sex or to form a “patriarchal unconscious”[1]. This shows the importance of an opposition to the male gaze to create a sense of power, though not privilege, for anybody who does not identify with the cisgender male. The male gaze is not derived solely from the sexual desire of men, it also accounts for the control that men acquire from being able to possess the image of the female, which is styled to their fantasies. These images, especially in advertising, show lack of realism as they are based on the fetishization of the female form. From removing skin impurities to showing the present idealised symbols of beauty, the image creates a fictional woman based around youth for the purpose of enticing men. This can be shown even through advertising based around feminine products. This creates an unhealthy mindset, helping to trigger certain mental illness such as anxiety and eating disorders. This harbours a divide between understanding reality and “simulacrum” (Baudrillard) [2]. For men, this can sometimes lead to more severe forms of fetishization through voyeurism, only deriving a sexual pleasure through obsessive watching of an unwilling participant rather than engaging in a relationship.

Photography relies heavily on the “scopopholic” referring to the way a female is perceived as an object rather than a subject of the photograph. In “Ways of Seeing” John Berger talks about female perception due to having to be viewed by men and becoming an “object of vision” [3] describing what women take from seeing a photograph of themselves being objectified. In “Seeing Eye to Body: The Literal Objectification of Women” [4] it is shown that when predominantly sexist males view images of women, often when they are less modestly dressed, it “results in reduced activation of the medial prefrontal cortex”. This is the same reaction which studies have shown occurs when the brain is looking at non-human objects. This not only shows that the male gaze is damaging but provides evidence towards the literal objectification of women. With these images being in the mainstream it creates a fictional reality, or a hyperreality, of what women truly are especially in young, susceptible minds.

On the other hand, Laura Mulvey explains how this is not the same for how men are perceived. “An active/passive heterosexual division of labour has similarly controlled narrative structure. According to the principles of the ruling ideology and the psychical structures that back it up, the male figure cannot bear the burden of sexual objectification.” This proves to be an interesting argument; suggesting that due to heteronormative standards of society, no matter how provocatively a male presents within an image he cannot be sexually objectified. This is because this sexual objectification of the male only furthers in supporting his role of power as he is not being portrayed as solely an object. Due to this being written in 1975 it is interesting to understand whether this statement is still relevant in the modern day where society is slowly becoming less heteronormative, and the narrative of the ruling ideology has somewhat shifted. According to “"With Ready Eye": Margaret Fuller and Lesbianism in Nineteenth-Century American Literature” [5] this ruling ideology works to exclude those who don’t conform to “gender difference” especially in terms of heterosexuality. To follow these rules of gendered ideology the male turns into the gaze of desire and intellect thus creating a situation where a woman is solely for affection and for the purpose of becoming an object of desire (Mary E.Wood). However, it may be argued by feminist Marxists that the dominant ideology hasn’t shifted far enough for the male image to be subjected to sexual objectification as they still hold the majority of power in society.

With social media there are many images that are now circulated without the given consent of the subject, this could lead to many such problems as obsession or manipulating the context in which the person allows themselves to be observed. In the subconscious mind this leads to promoting the male gaze in the modern world over resolving problems known to many. With the anonymity involved with this, these photographs often go unchallenged and even though they are not in the mainstream media it still begs a moral question as to whether this form of candid photography should be promoted even if not inherently pushing the more commonly known aspects of the male gaze.

Photography is one of the most widely spread forms of art in the modern day, spread through the means of production such as advertising and social media. In “Decoding advertisements : ideology and meaning in advertising” [6] it talks about how in certain advertising there is a clear divide between being seen as a woman and as someone who has a career. This describes that while being a woman you cannot have a serious career such as being a “bio-chemist” otherwise you are no longer seen as feminine. As it is highly consumed by younger generations, now more than ever this raises the importance to break the societal norm of the male gaze and change awareness of self though photography.

One of the most impactful and important challenges to the male gaze is that of female self-portraiture. In “Revealing Habitus, Illuminating Practice: Bourdieu, Photography and Visual Methods” [7] according to Paul Sweetman the discussions of Bourdieu suggest that photographs serve the purpose of relaying a habitus in a non-verbal manner. Photographs can explain in ways, that words may not be able to, how people can relay and reproduce certain cultures and ways of living. However, as discussed in “Improvisation within a Scene of Constraint: Cindy Sherman's Serial Self-Portraiture” [8] self-portraiture challenges normalcy by showing harmful behaviours passed through generations. Cindy Sherman relays the habitus through fictional characters that she portrays in her self-portraiture with their exaggerated femininity. The characteristics that she portrays in these photographs aren’t particularly orchestrated but more likely pulled from memory and shared culture (Michelle Meagher pg9). As it is in photographic form it helps to portray the harmful stereotypes placed onto women in a more shocking format.

Female directed photography is important for the growth of the industry to include more perspectives, specifically female photographers taking photographs of females. There is a rise of female photographers now, changing the narrative that photography is a male orientated field. Female voice is important to break down heteropatriarchy. As discussed by Charlotte Jansen in “Girl on Girl” [9] although the aim is to have an equality between genders there is a necessity to solely highlighting that of female photographers taking photographs of women due to having a long way to go before an equality is established. Such as the “Bechdel Test” [10] in film where two females can hold a conversation where the topic doesn’t involve a man, there is female gaze in photography, a way of making photography without having men as the target audience. As Zing Tsjeng discusses, the female gaze may not have a definition yet, but it can be described as a way of looking without objectifying and without the embarrassment normally linked with a female nude body. [11] The importance of female self-portraiture is that the message isn’t corrupted through someone else’s perspective. The body and subject portrayed in the photograph is their own and thus is a justified way to express power in identity.

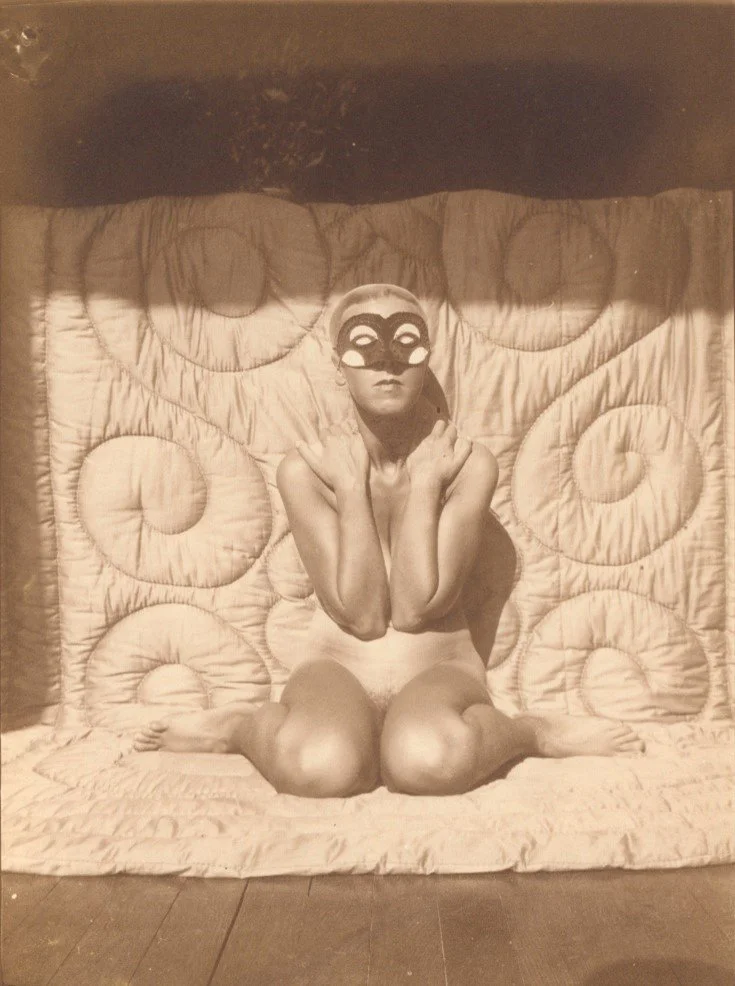

An early example of breaking the heteropatriarchy through self-portraiture is the feminist surrealist photographer Claude Cahun (1894-1954). Facing six months of Nazi imprisonment due to the possession of a camera and being sentenced to death for treason she turned to other art forms such as writing to express herself, but this doesn’t by any means diminish the photography she produced, referring to these many times in her writing. [12] Her work was made when dominant surrealistic photography in the early twentieth century heavily featured the prioritisation of the female nude, whereas her surreal self-portraiture presented herself as naked but never as “nude”. This was for the purpose of protecting herself from “voyeuristic consumption”.[13] In a time where it was so prevalent to see the sexualised image of a woman it was even more important to see representation of self-portraiture that turned away from the classic images based around male control, for example photographs produced by Man Ray as shown in figure 1. Photography during this period was often directly related to the objectification of women, even in a surrealistic format.

In comparison to Man Ray’s portraits of women, Claude Cahun portrayed herself with power despite the underlying misogyny in surrealistic photography at that time. An example of misogyny during the surrealistic movement of this time was Andre Breton saying that women had no say in the matter of sex, despite there being several intellectual women involved with the movement. [14] Claude Cahun was set on the task of investigating herself when she was already the subject of an objectified gaze (David Bate pg8).

Figure 2 shows a self-portrait of Claude Cahun from 1928. This is perhaps the most revealing in terms of her self-portraits and yet it still directly challenges the male gaze. With the mask partially over her face there is a protection of her identity, meanwhile she obstructs sexualised body parts while not making herself smaller. Masks played a big part within her self-portraiture having stated herself “Under this mask, another mask,” [15]. The mask serves to represent different identities involving gender differences and mental stability. Her images express an androgyny or as referred to in “Mise en Scene” [14]as a “third gender”. Due to the pseudonym Claude Cahun, gender is removed from her name as well as her photographs, taking away more opportunity for objectification. Her images however would not have the same affect had they not been self-portraits as it was the power in her choice to take the image that challenges the male gaze.